The role of a publisher in the dissemination of thought cannot be overemphasised, and the immortalization of one’s literary work is a dream of every writer. For a second, just imagine the inexistence of a publisher: knowledge would have been a scarce commodity. Publishers are not just business gurus, but important agents of change who advance society by sharing meaningful ideas. As cultural entrepreneurs, they contribute to the visibility of culture and the establishment of a language through the knowledge products and books they publish. Moreover,

“the health and vitality of a language are not just influenced by the number of speakers, but also by the number of writers and publishers”.

The spoken word can easily be forgotten and fade away, but the written word lasts longer. Writing is the most ancient method of preserving knowledge for contemporary and future generations. As such, publishers of books are contributing to the immortalization of not just the knowledge of which books are written, but also of the language and medium through which that knowledge is communicated. Thus,

the preservation of a language largely hinges on the Trinity – Speakers, Writers and Publishers.

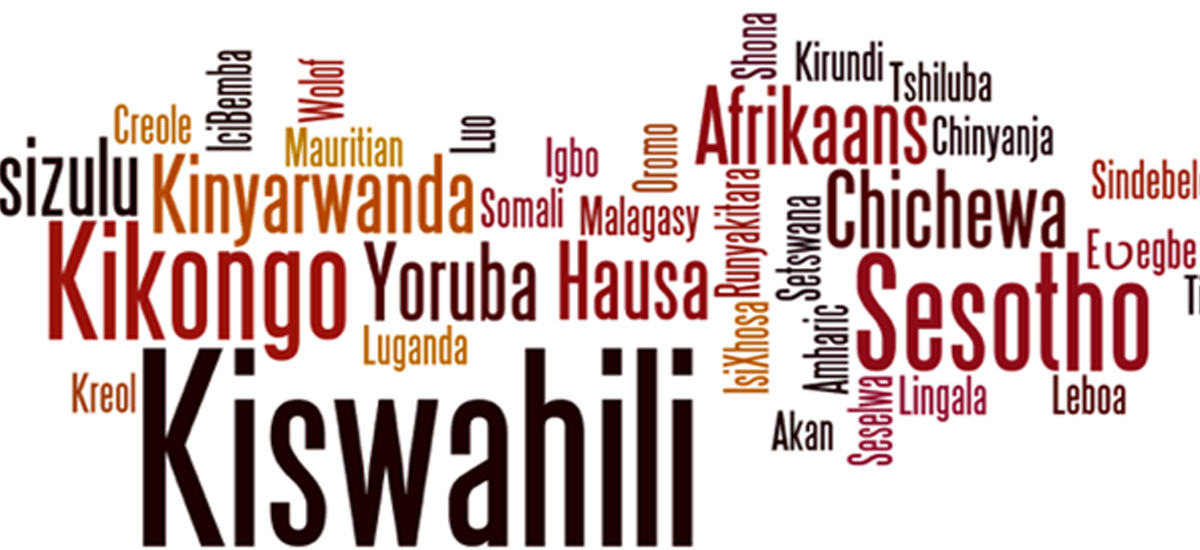

Therefore, when it comes to the promotion of African languages, the number of people able to write and publish regularly in those languages is also key.

But when one looks at the book industry in Africa, one can easily notice that the number of books published in foreign languages outshines those published in local languages.

It’s easier to find a Shakespeare in Africa than a Ngugi Wa Thiongo.

This is sad, yet true; the reality calls for a more strategic and holistic valorization of African languages through any possible medium, especially in education and publishing. In this write-up, i share key strategies that publishers can use to promote African languages and contribute to their visibility and use.

1. African publishers should bet more on writers who write in African languages

During an interview with world-renowned Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ Wa Thiong’o, Nanda Dyssou, a Congolese-Hungarian journalist, inquired why there are still not enough books in African languages. She indicated that it was one of the reasons why people are used to reading in English and other European languages, and blatantly recognized that

African publishers are less likely to take a chance on writers who write in their native language.

In his response, Ngũgĩ[1] said that “getting published is one of the most infuriating challenges of writing in African languages. There are hardly any publishing houses devoted to African languages”. So writers in African languages are writing against great odds: no publishing houses, no state support, and national and international forces aligned against them. Literary awards such as the Nobel, Commonwealth Literature, and even the Africa-centric Noma prizes rarely go to writers in African languages that are, after all, spoken by the majority of Africans.

Prizes are often given to promote African literature, but on the condition that the writers don’t write in African languages.

Many African writers can write in African languages, but are afraid of not getting published. This obstacle, if removed by publishers, will encourage writers to write more in African languages; which will contribute to an influx of literary works in African languages. Again Ngugi Wa Thiongo, remains a global African writer who has consistently challenged statu quo by continuing to use Gĩkũyũ as his written language of choice, and he even asks his publisher to wait for two years before releasing the English translations of his books to give Kenyan readers more time to discover the story in the original language. “The publishers are not always with me on this policy,” he said.

At Kabod, we believe this will ultimately promote African languages and increase the lifespan of the languages used. And to make that possible, we have discounted prices and special offers for African publishers or writers who want to translate their books or writings from any European/Asian languages to an African language.

2. Creating more dedicated publishing houses focusing exclusively on writings in African languages.

One radical [but costly] decision that can be made by publishers is to either institutionalize publishing houses that focus only on the publication of content in African languages, or at least have a unit in their publishing house that focuses on the publication of literary works in African languages. This is a sacrificial and financial risk. However, for the greater cause of promoting and preserving African languages, it is worth the price.

In light of paying the price, there are some initiatives working tirelessly to support African language publishing. An example of an initiative that focuses on publishing in African languages is WritePublishRead, in collaboration with the African Languages Association of South Africa, which aims to give unpublished local writers of indigenous language fiction the chance to be published digitally in their home language by way of a self-publish starter kit, thus enabling anyone to read these texts if they have access to a mobile phone or any other digital device.

Another is the Children’s Book Project in Tanzania, which seeks to improve literacy skills amongst school children and encourage a reading culture in the country. It also focuses on equipping libraries with quality reading and learning materials (including African language materials) and supports the Tanzanian publishing industry to produce quality books for children and young people.

In South Africa, Nal’ibali is an initiative that promotes reading and writing in mother tongue languages, and champions the reading-for-enjoyment campaign to ignite children’s interest in storytelling and reading. Publishers’ collaboration with initiatives that promote African languages paves the way for the promotion of the languages while making money.

We can’t expect African languages to grow in preeminence, status, and global influence without being willing to pay the price.

If that would require publishing books in African languages with the risk that very few people[2] will purchase them, publishers and governments must be willing to take those risks and consistently promote the publishing in and use of African languages. Increasing the number of books published in African languages is crucial to developing a strong local book economy and reversing the declining trend. For example, in 1981, “the vast continent of Africa, with 10% of the world population, produced a meagre 2% of the global output of books’[3]. A decade later, Africa’s share was 1%, with 70% of its books’ needs imported.

“Publishing in African Languages: Challenges and Prospects” is a very useful book which explores the trends, problems, and opportunities of publishing in the many and varied languages of Africa from the various perspectives of publisher, writer, and state, and raises important themes for you to ponder.

Philip Altbach, a specialist on African publishing, makes a strong case for the continuing viability of publishers publishing in African languages and recounts their major problems: dominance by colonial languages (Portuguese, Spanish, English, and French) that are still favoured by ruling elites; the high cost of special typography for tonal differences in non-standardized scripts; the political difficulties of privileging one language over another (as in Cameroon, for example); cross-border linguistic tensions; the limited purchasing power and low literacy rates of readers; and limited markets.

These challenges, however, should not be a reason to stop, but an incentive to be more ingenious, strategic, and hard-working to ensure that African languages are not only used in present times but also preserved for the next generation.

3. Network with African Language Translators for the bilingual translation of books.

Evidently, myriads of literary works have been written and published by Africans. Most of these literary works written by Africans are in European languages such as English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese and not in African languages. Partnering with African language translators to translate these literary works into African languages will have a greater impact on African readers.

The above words of Nelson Mandela reveal the secret of speaking to one’s heart.

Imagine reading Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart in Yoruba or Igbo as a Nigerian – you will relate much better than reading it in English because the setting is Nigerian, and it is written in a Nigerian language, or imagine reading Grief Child by Lawrence Darmani in any Ghanaian language.

The African Language Association of Translators and Teachers (ALATT) is a LinkedIn group that has individuals from across Africa working in African languages as members – connect with them if you need African language translators. This article by the executive director of Muna Kalati, Christian Elongué, also presents some initiatives related to the translation of children’s books into African languages.

Well-known publisher Aliou Sow (Editions Ganndal, Guinea) suggests that more trans-border co-publishing in African languages (such as Pular across a wide region of West African Francophone, Anglophone, and Lusophone zones) could break down barriers erected by colonial borders. Authorities should stop regarding national languages as dialects, and intellectuals should be more involved in the development of such languages.

4. Organising writing/reading competitions in African languages

Organising competitions or award schemes is one sure way of getting the masses to participate in a cause. Naturally, human beings are motivated to give their all for a cause when they know there is a reward lying before them. In Ghana, competitions like the National Science and Maths Quiz, Spelling Bee, Reading, Debate, Sports competitions, etc., have great crowds and attract many sponsors.

Publishers’ organising similar competitions (poetry, drama, reading, writing, and storytelling competitions) that focus on African languages with amazing incentives will encourage people, especially the youth, to advance their proficiency in their native languages. For example, let us mention the Safal Cornell Kiswahili Prize for African Literature, which focuses on writing in African languages and encourages translation from, between, and into African languages. The award has a value of 15,000 US dollars for its winners. Awards such as this can be organised in each African country – making it a national project that promotes the languages spoken in the country.

5. Engage policymakers to invest and support more indigenous publishing initiatives.

Getting political support and collaboration is essential for the success of any nationwide initiative in Africa. Many interesting projects that aimed at boosting the reading culture, have drastically failed because government officials were not involved enough: either out of disinterest or lack of strategic partnership. Three or more decades of shameful government neglect of public library services in Africa is another reason why African language publishing is not flourishing.

In most African countries, public library services have traditionally been the biggest purchasers of African language titles in the past, but many public library services now operate with pitiful book buying budgets, or new acquisitions have ceased altogether. African government officials usually view book donations from abroad as the most economical method of providing books to their libraries, at no cost to them. They do not seem to see a need to provide public libraries with book acquisitions budgets, because their national library services are happy to receive regular donations from book aid organisations of the North, which frequently include huge quantities of culturally inappropriate titles

Since everything rises and falls upon leadership, it is therefore critical to always and wisely associate political forces through strategic advocacy.

In South Africa for example, we have the Indigenous Languages Publishing Programme, which is a government sectorial priority implemented by the South African Book Development Council. It aims to stimulate growth and development in the book sector, increase indigenous languages publishing, support the ongoing production of South African authored books in local languages, and assist small and independent publishers to produce quality indigenous language books. It funds up to 50% of the cost of publishing the books, while the publishers incur the remaining costs. This programme therefore shares the risks that publishers ordinarily carry on their own when publishing to new markets.

Another project is a reprint programme of South African classics in indigenous languages. The project, coordinated by the Centre of the Book at the National Library of South Africa, has reproduced a total of 68 titles, in nine indigenous languages, many of which were no longer available in the public domain.

Conclusions and recommendations

Preserving and promoting African languages is the responsibility of every African; writers, speakers, publishers, and African language teachers. The publisher’s role in promoting African languages is indispensable. Aside from increasing publishing in African languages, I also suggest that:

- Language policy debate should be depoliticized

- There should be incentives to train and deploy more teachers of African languages

- Students should have greater choice to be examined in standards of their own languages.

- The state should assist with translation services (the greatest cost faced by the industry) to facilitate investment by publishers in indigenous languages.

Whilst, in the face of Africa’s escalating economic and social problems, it is difficult to be overly optimistic about the future of African languages, this is an area where Kabod and others engaged in the processes of teaching, learning and communication might make a tangible contribution.

[1] Ngũgĩ’s most recent novel, The Perfect Nine, was also the first written in an indigenous African language to be long listed for the International Booker Prize.

[2] It is estimated that only ten to twenty per cent of Africans are fluent in African languages. Read: C. Limb Peter, “Limb on Altbach and Teferra, ‘Publishing in African Languages: Challenges & Prospects,’” accessed August 19, 2022, https://networks.h-net.org/node/15766/reviews/16691/limb-altbach-and-teferra-publishing-african-languages-challenges.

[3] Amadio Arboleda, “Distribution: the neglected link in the publishing chain” in Philip Altbach et al. (eds.), Publishing in the Third World: Knowledge and Development. London: Mansell, 1985, p.47.

I’ve been in the language industry since 2018 mostly working as a freelancer and have also worked in some international organisations as an in house translator. I am a certified translator with (English, French and Arabic) as my language combination. I have gained experience working on various projects in different fields of study. With a high proficiency in my language combination coupled with my experience over the years, i have gained the skill of delivering excellent and timely translations.